The last dance

The «La Paloma» ballroom was originally an iron foundry known for sculpting the statue of Christopher Columbus, created for the 1888 World’s Fair. It is located on Tigre Street, on the edge of the Barrio Chino or Raval, near Ronda Sant Antoni. The doors of this ballroom opened in 1903, and since then, it has attracted a large number of visitors. After the demolition of the Apolo ballroom in 1990, La Paloma is now the only remaining venue of its kind and the oldest in the city.

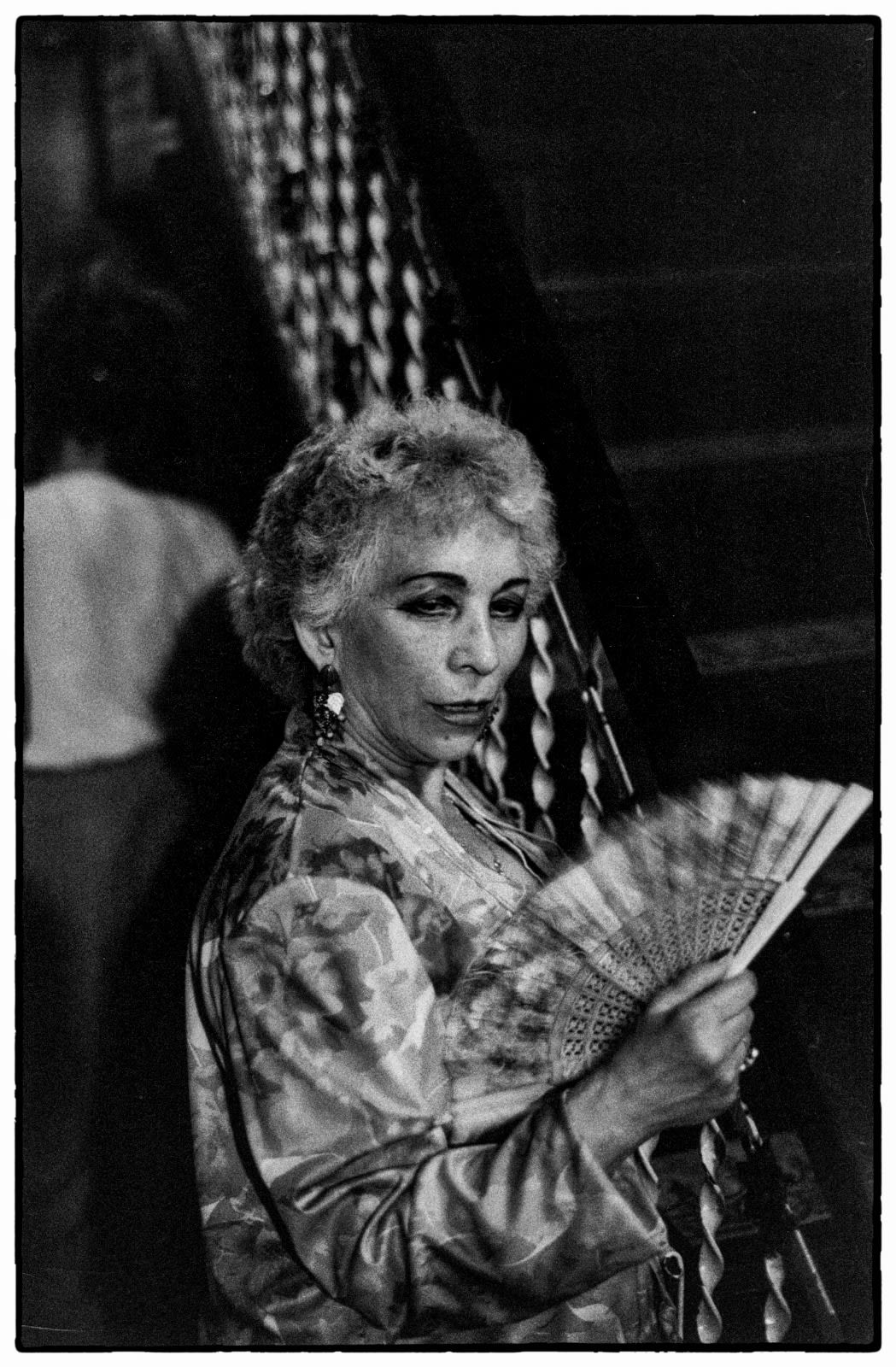

From Thursday to Sunday, «La Paloma» is a mandatory destination for waiters and waitresses, public employees, young people, retirees, students, and the unemployed. Tonight, the line is long. Maria Antonietta waits patiently for her turn. She greets a few older men behind her with a wide smile. They are very well-groomed, with freshly polished shoes. She, too, is dressed in her best attire. She wears a turquoise embroidered silk dress in the style of the 1950s; low-heeled blue shoes, a pendant adorning her bare neck, and matching earrings.

The heat of this summer is humid, as always in Barcelona, and bodies feel sticky. At the entrance, two fifty-year-old men in black tuxedos and slicked-back hair joke with the regulars. Many of them have not missed a single weekend at La Paloma for years. The dimly lit hall is packed, and some couples discreetly take their places on the second floor. The orchestra, composed of men in white shirts and black bow ties, makes its entrance. They start, as usual, with a soft waltz. The men eagerly rush to invite ladies to the dance floor. The women, just arriving at the ballroom, barely have time to take off their coats.

Maria Antonietta begins to dance alone. With her eyes closed, she remembers the events and people who frequent La Paloma. She has just turned 65 and has lived in Barcelona for more than four decades.

II

At times, the atmosphere of La Paloma recalls the popular «patacada,» a traditional workers’ celebration from the 1800s. During these events, people danced, shouted, and drank until they collapsed. The organizers were forced to hire guards to prevent the parties from turning into endless drunken brawls.

Manolo, the waiter, offers me a cold beer as I look around with curiosity and amazement. “There hasn’t been a real fight here in a long time. People come to La Paloma to have fun, not to cause trouble,” he says in a voice that sounds more like a whisper.

He started working at La Paloma more than 25 years ago and knows everything worth knowing about Barcelona, not just the gossip told in dance halls but also about its recent history. In the 60s, he worked as a photojournalist for the city’s main newspaper, El Noticiero Universal, which later went bankrupt. He used to meet other photographers in the streets of Raval, among them Joan Colom and Català-Roca. “I’ve been close to the most significant events and scandals in this city,” Manolo says with a somewhat mysterious tone, without going into further details. A moment later, he takes my arm and leads me to the table of a woman known as «La Condesa Macarroni,» another famous regular. “Come stai, bello?” she greets me with a Neapolitan accent as she extends her hand. Despite being 80 years old, every summer, she leaves Italy to come to Barcelona. La Paloma is the only reason for her visit. She says she misses this city, still nostalgic for its beginnings in the early 1900s. “Being in Barcelona is like waiting to be seduced, it’s feeling young forever,” she confesses.

With lively eyes and cheeks loaded with makeup, her necklace reaches her waist despite several turns around her neck. On her head, she wears a large hat with flowers and fruits. “What sign were you born under?” she abruptly asks me. “Libra,” I reply, somewhat perplexed. “Do you know what day you were born?” “A Sunday.” The Countess immediately draws my future and offers me advice on which women I should meet and which profession to choose. She assures me that since childhood, she has had clairvoyant abilities, that her capacity is supernatural, and that many of her friends from her village in southern Italy still ask her to read their palms. «Did you know I predicted the moon landing and Princess Diana’s accident ten years in advance?» she boasts.

Many «countesses» who have passed through La Paloma are well into their years. Manolo remembers a Catalan woman who came until after the age of 86, and another, Julia from Seville, who didn’t stop attending until she was 96. “All of them came to La Paloma until they could no longer walk,” he assures.

III

The musicians continue with a cha-cha-cha and later with a tango, a dance that was introduced to Barcelona in the 20s and 30s, just like in Buenos Aires and Paris. At La Paloma, during those years, the famous trio Irusta-Fugatoz-Demare was very popular among the city’s workers. Even Carlos Gardel traveled several times to the city, where he recorded more than 50 records. But not everyone approved of this trend, as it provoked heated criticism in the conservative local press, which rejected its erotic and seductive forms.

Nevertheless, the tango survived, and tonight it dominates the party. When the deep tones of the bandoneón’s first notes are heard, a man with long gray sideburns invites a robust blonde woman in her thirties, clad in a tight blue dress, to dance. The couple dances slowly and sensually. The man tries to embrace her while following the well-rehearsed steps of the tango. After a moment, the couple takes center stage. He shows off his skill by placing one leg between her thighs, spinning 90 degrees, and with great precision, takes an elegant step in the shape of an eight. The bandoneón continues to set the rhythm while, just a few meters away, a couple of lovers admire each other, reflected in the large mirrors on the dance floor.

Maria Antonietta doesn’t tire. She continues to dance alone as if in a trance in front of the orchestra. The people and the world around her seem nonexistent. The stage light falls obliquely on her face. Tonight, she is the star. She thinks of all the men she has met at La Paloma, her first love, moments of happiness, and all those unnecessary farewells.

IV

In the twenties, when she started going to the dance hall, La Paloma had already been the favorite place for workers and immigrants in Barcelona since the beginning of the century. There, industrialization had reached levels superior to the rest of Spain’s cities, and thousands of peasants had migrated to this modern metropolis, leaving their villages in Andalusia, Aragon, Extremadura, and Murcia in search of better opportunities.

The giant chandeliers, the walls and ceilings decorated with various regional dance motifs, the neo-baroque finish of the balconies and boxes around the dance floor were so striking that they made La Paloma a sublime stage setting. But after a few years, the venue lost some of its magnificence: the walls were covered with white lime, and the beams, which had been ornately covered, were left exposed. In 1915, it was decorated «à la française,» as dictated by the fashion of the time, and in 1919, it was decorated with plaster sculptures of various styles. Until the 50s, the venue was packed, but since then, it began a decline that continued throughout the 60s and 70s. «We had to organize boxing nights to attract the public,» Manolo recalls with a smile on his thin, sharp face.

V

Maria Antonietta knows she won’t return to La Paloma. Barcelona is no longer profitable for her. Picking up clients on Las Ramblas is almost impossible, especially after the 1992 Olympic Games. Several factors drove customers away from Las Ramblas. Fear of AIDS, which settled in those years, made them prefer safer places like the so-called «relaxation institutes» and clubs that advertise their specialties in the commercial pages of newspapers. Simultaneously, the neighborhood was invaded by transvestites who, along with immigrant girls from Africa and Latin America, took the market away from local workers like her. To top it off, junkies arrived, and the area became increasingly violent.

La Rambla de Santa Mónica, like the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, is now completely taken over by transvestites who gossip in the bars of the Raval’s inner passages. Their buttocks and breasts are inflated with cheap silicone injected by amateurs who improvise surgeries with all the risks that entails. There is no other option: resources are lacking to get better substitutes of French manufacture.

Among them, the transvestites call each other by their nicknames: Marilyn, Sophia, Sara Montiel. On weekends, they have their own show in some of the neighborhood bars, resisting constant police raids that have failed to expel them from Las Ramblas.

VI

Behind the bar, I continue my conversations with Manolo about the decline of the Raval. “The old Paloma is also dying slowly, and unfortunately, it’s inevitable,” he tells me. “It’s not like in the mid-80s, which were the best years.” Meanwhile, he serves some beers and quickly glances at the crowd in the venue, as if trying to spot someone among the regulars.

“Are you going to stay long?” he suddenly asks me. “Maybe for another year,” I answer. “Are you familiar with the neighborhood, have you walked around its streets?” he continues. “I’ve gotten to know it a little, although at times it’s confusing,” I reply. “I’m not surprised,” he says in a low voice. “This neighborhood has been through a lot.”

After a short pause, he adds, “One of the oldest dance halls in Barcelona, Fornos, used to be on Calle Escudellers. The most elegant prostitutes in the city used to meet there with sailors, soldiers, police officers, and thieves. Today, that area is full of Pakistani bars and exchange offices. We won’t be here for long either. This place is changing very quickly, and not necessarily for the better.”

I watch the couples dance. I follow Maria Antonietta with my gaze. I wonder how many lonely, aging women have passed through these doors, looking for the men they loved, time and time again. Perhaps they still seek them. Perhaps they come to find the memory of their early years, of a Barcelona that no longer exists. Even La Paloma, that building with the charm of the Belle Époque, will close its doors in a few years. Only a plaque will remain to recall the ballrooms of the working-class neighborhood of Raval.

VII

“El Tigre” has been a regular at La Paloma for over four decades. Everyone knows him. Around 70 years old, short and stocky, almost bald, he is an enthusiastic dancer who always invites the most beautiful women to the floor. There’s no way to avoid him, as he never accepts a refusal. But tonight, he dances alone, moving his short arms like windmill blades, competing with Maria Antonietta for the spotlight in front of the orchestra.

Antonio, another regular, approaches and offers me an Estrella beer. He prefers a Boldán, which is a bit stronger. His current address is a cell in corridor seven of the Modelo prison. He has weekend leave. As usual, he celebrates it at La Paloma, where he feels safe and free from judgmental looks. He notices that I have a small camera with me, and after a moment, he carefully asks if I could take a photo of him. “But not when I’m dancing, because I don’t know how to dance,” he warns with a shy smile.

Gustavo, or “The Electrician” as they call him at La Paloma, insists on having a photo taken with his new girlfriend, Conchita. They first met here a few weeks ago. Now, they come every Friday, and he would like to have a picture to commemorate his good fortune. “The Electrician” is a rock fanatic. His thin body seems to be made of rubber, twisting as if possessed by the devil. Conchita is more discreet and dances like a whirlwind around Gustavo.

The orchestra now begins a sevillana. Paquita runs to the floor, brazenly inviting the guys to dance. Many refuse for fear of making a fool of themselves. Paquita is around 25 years old and works as a waitress in a nearby bar. Among her closest friends, she’s known as the “man-eater.” “But nobody comes to La Paloma to pick up guys,” she says with a mischievous glint in her eyes. She always arrives accompanied by Alicia, an older woman whom her friends call «godmother.» Alicia is Romani and lives in Raval. With thick black hair and lively eyes, she dances gracefully despite her large and heavy frame. «Olé! Olé!” echoes throughout the hall. The younger ones form a train that zigzags between chairs and tables.

The singer, a middle-aged man with a progressively hoarser voice, collapses from exhaustion in a chair. The night ends with Strauss. Everyone is tired, but they don’t give up the last waltz. The giant lamp in the center of the hall flickers to signal the guests that the dance is over. The waiters hurriedly collect bottles and glasses scattered on the tables.

Maria Antonietta approaches a young couple who celebrated their wedding in the hall. She kisses the bride and wishes her good luck in life. The orchestra has already left the stage. Maria Antonietta thinks of the train waiting for her at Barcelona’s Sants station. She will leave the city forever. No one wished her good luck on this, her last night at La Paloma. She doesn’t want to stop dancing alone, with her eyelids closed. The heat melts the mascara, now streaming down her cheeks like a sweat of dark blood.

Text and photos: Patricio Salinas A